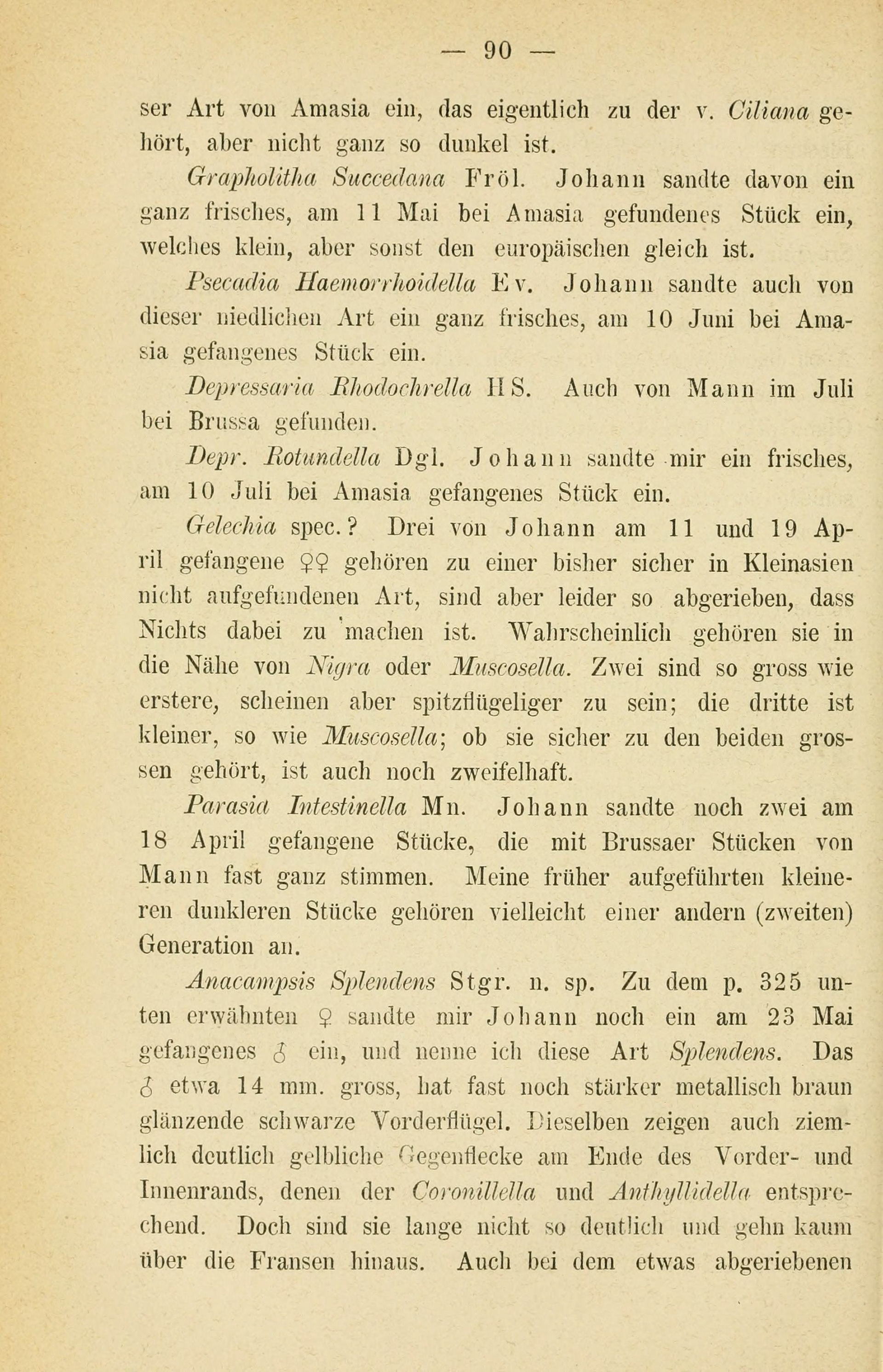

1862-1942, Niksar (Tokat), Amasya, Istanbul, Heidelberg, Berlin,

Aintab (Gaziantep), Merzifon, Istanbul, New York, Detroit

Aintab (Gaziantep), Merzifon, Istanbul, New York, Detroit

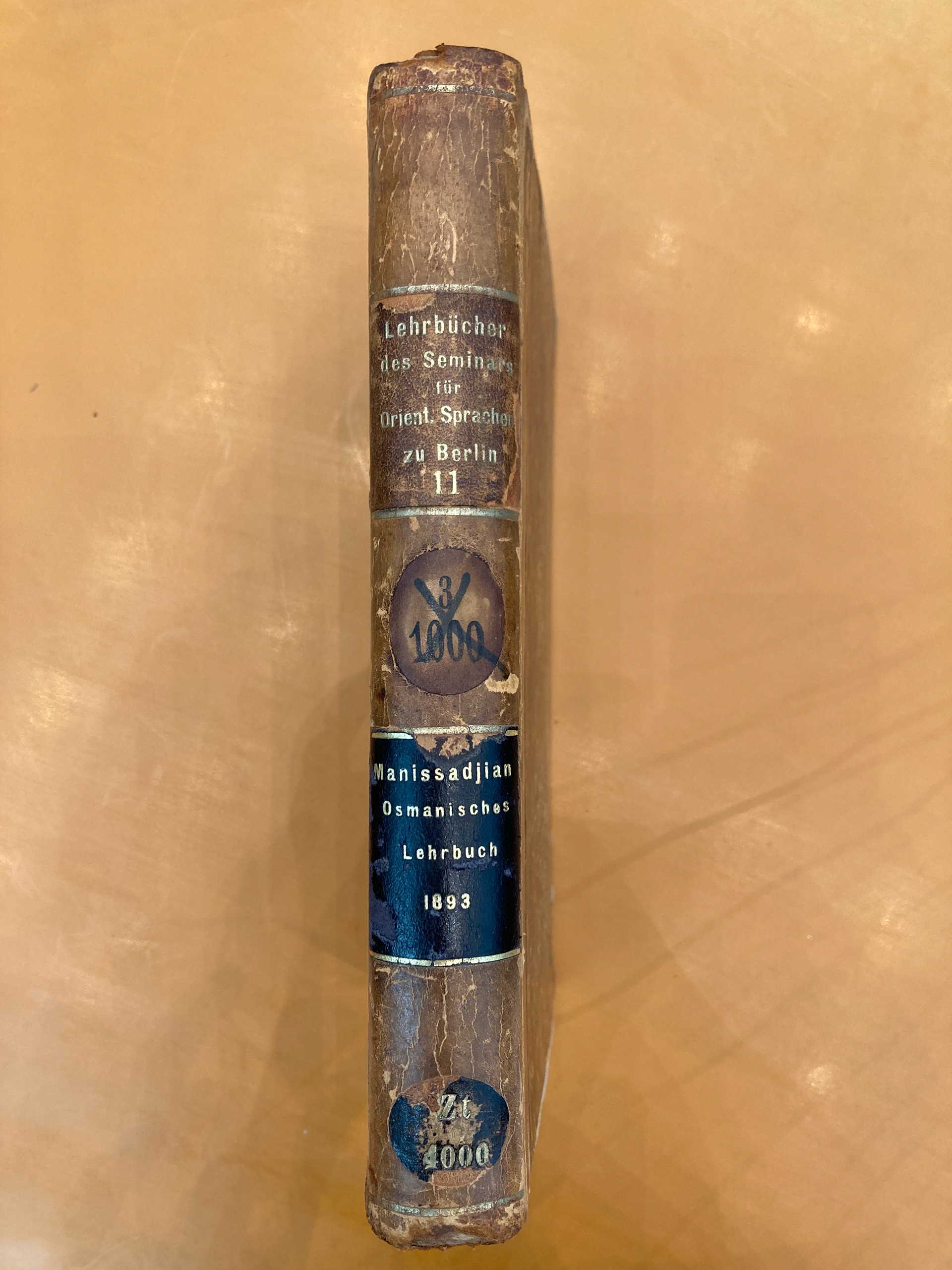

1893, Photograph of University Teaching Book on Ottoman Empire Studies “Osmanisches Lehrbuch” written and published by Manissadjian when he was teaching in Berlin Source: Staatsbibliothek Berlin, Photo: Prof. Dr. Nazan Maksudyan

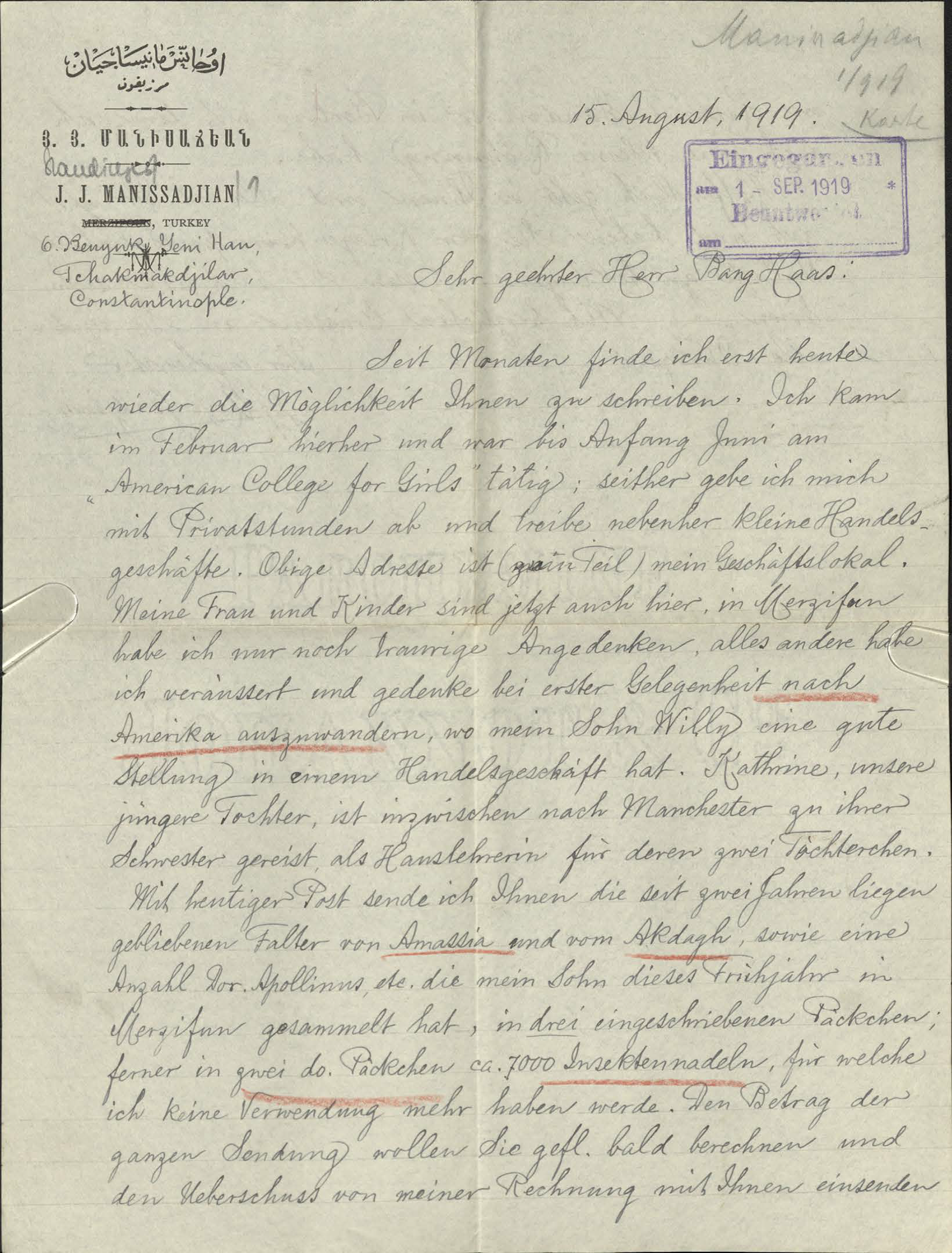

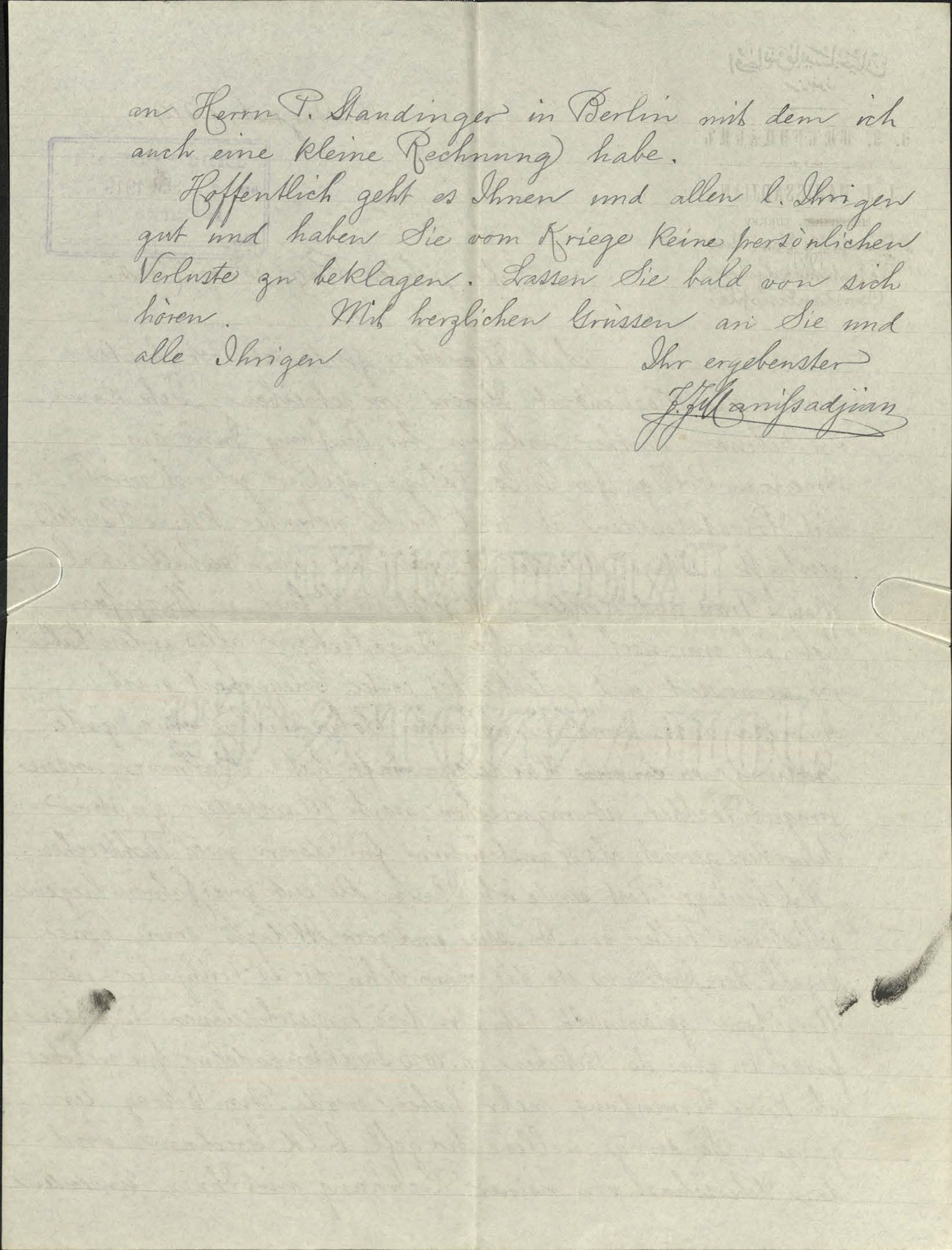

1919, Letter from Manissadjian to Andreas Bang-Haas, winding down his professional passion before final emigration to the U.S. Source: Handschriftenabteilung der Staatsbibliothek Berlin, photograph: Prof. Dr. Nazan Maksudyan

1919, Letter from Manissadjian to Andreas Bang-Haas, winding down his professional passion before final emigration to the U.S. Source: Handschriftenabteilung der Staatsbibliothek Berlin, photograph: Prof. Dr. Nazan Maksudyan

Portrait of Manissadjian, taken in Aintab, in the studio of H. Hovhanness, ca. 1883. Source: Handschriftenabteilung der Staatsbibliothek Berlin, Portr. Slg./Philol. kl./Manissadjian, Johann J.; Nr. 2. Photo: Prof. Dr. Nazan Maksudyan

![Portrait of Manissadjian, taken in Berlin, in the studio of H. Noack, August 16, 1890, dedicated to Miss A. Grabow. Source: Handschriftenabteilung der Staatsbibliothek Berlin, Portr. Slg./Philol. kl./Manissadjian, Johann J.; Nr. 3 [1890] Prof. Dr. Nazan Maksudyan](https://cdn.myportfolio.com/c01b99f7-1a13-4e71-9cfe-151253fc7be0/180da598-892f-4713-908b-1f132ca399ec_rw_1920.png?h=e328e8dbb00c26ea56be28a630f2937a)

Portrait of Manissadjian, taken in Berlin, in the studio of H. Noack, August 16, 1890, dedicated to Miss A. Grabow. Source: Handschriftenabteilung der Staatsbibliothek Berlin, Portr. Slg./Philol. kl./Manissadjian, Johann J.; Nr. 3 [1890] Prof. Dr. Nazan Maksudyan

A Life of Knowledge, Collaboration, and Loss

Johannes Jakob Manissadjian (1862–1942) was a scientist, educator, and naturalist whose life embodies the entanglement of cultures, knowledge exchange, and historical disruptions. Born in Niksar (Tokat) to a German mother and a Protestant Armenian father, he grew up multilingual, speaking German, Armenian, Turkish, and English.

A Scholar Between Worlds

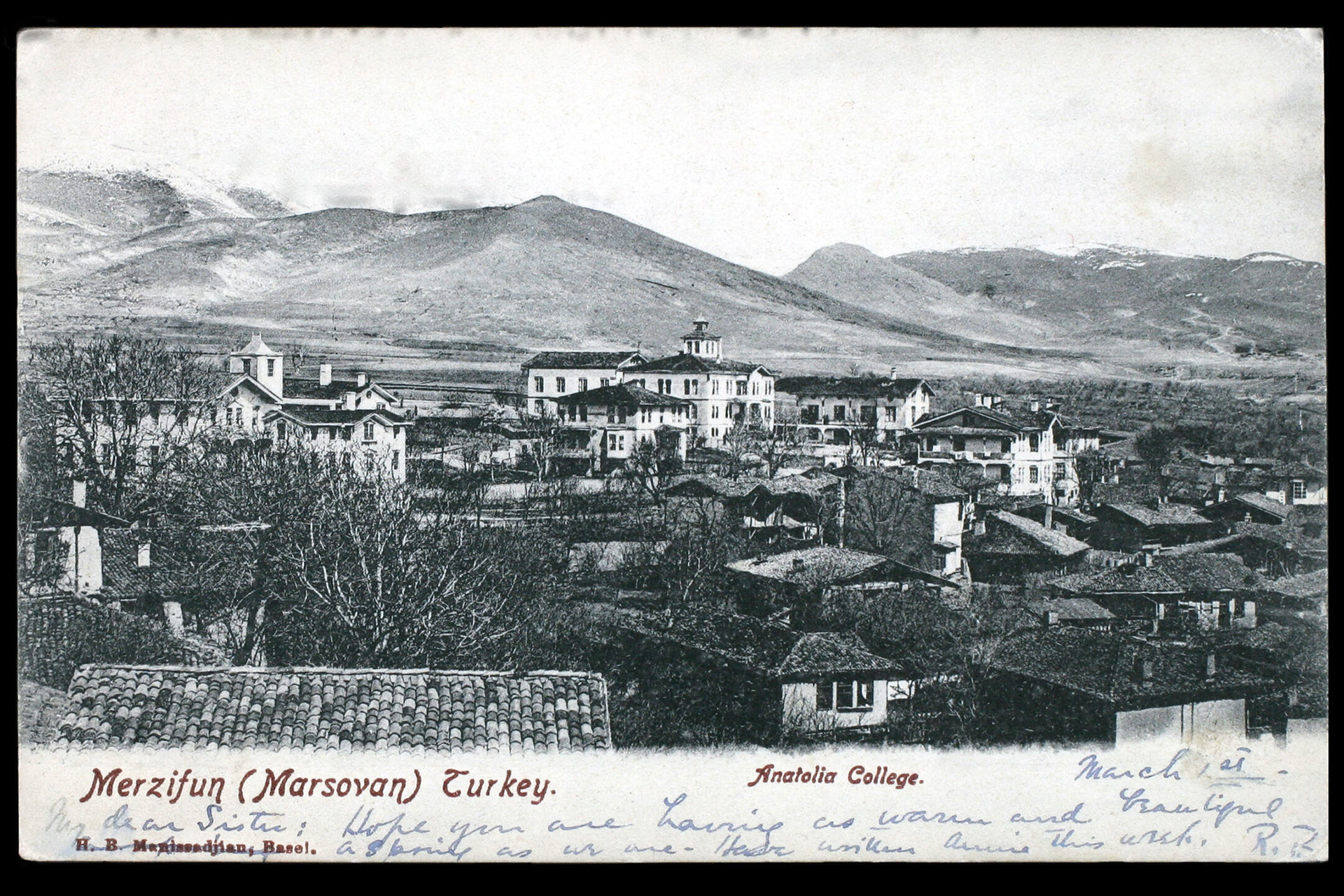

Manissadjian studied in Germany at Heidelberg and Berlin before returning to the Ottoman Empire to teach at Anatolia College in Merzifon (1890–1915). He established a meteorological station and a natural history museum, amassing over 7,000 zoological, botanical, and mineralogical specimens. His scientific research gained international recognition, and he collaborated with leading German scholars like Otto Staudinger. Who refers to Manissadjian as „Johannes sendete mir“ in his research. Manissadjian’s linguistic expertise also led him to teach Turkish at the Seminar for Oriental Languages in Berlin.

Genocide and Displacement

Manissadjian’s career was abruptly disrupted by the Armenian Genocide in 1915. While most of his colleagues and students were deported and killed, he survived due to missionary intervention and forced conversion to Islam. He never recovered from the atrocities he had experienced around him. His museum was dispersed and discontinued, symbolizing the destruction of both Armenian heritage and indigenous scientific knowledge. Manissadjian’s detailed recording of each object in the Museum 1917–1918 was his resistance to the impending post-catastrophe anonymity of the collection. In 1920, he fled to the U.S., where he withdrew from academic life, though he preserved knowledge by publishing Proverbs of Turkey, an ethnographic work on Anatolian culture.

Uncovering Hidden Histories

In a museum setting, his story offers visitors a lens to understand the interconnectedness of past and present. His work challenges the notion of rigid national identities, instead showcasing a world where knowledge and culture thrived through cooperation and coexistence—until shattered by violence. By remembering Manissadjian, we also confront the silences imposed by history and restore visibility to those whose contributions have been erased.

Source:

Maksudyan, Nazan: The genocidal disruption of Johannes Jakob Manissadjian’s (1862–1942) lifework: a biographical approach to mass violence and indigenous knowledge production, open access, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1080/20581831.2024.2375930

Postcard from Manissadjians Anatolian College in Merzifon, undated Source: SALT Research, undated